New Mexico

A Picture Can’t Stop Time

Art can transport you to another place. It can pause time. But it can’t stop it. Yes, I’m on about time again, because on our New Mexican ramblings I got to see two places I assumed art had immortalized.

The first was the site of the adobe church in Hernandez where Ansel Adams famously captured a lonely moonrise. It’s my favorite of all his images because I’ve always imagined this desolate, remote place as protected, looked over each night from above. I’m not religious but this photograph explains why people have faith. It reminds me of the aloneness I felt as a kid living on the road with nomadic parents. No matter how far from home we traveled in our dilapidated camper the same moon still rose and set above me.

Ansel Adams could not make his photograph today. The dirt road where he set up his tripod to capture the moonrise is now a four-lane highway, minutes from a sprawling, dusty city called Espanola. Even under the glow of a rising moon you couldn’t see the church’s cross from the road’s high vantage point because it is obscured by ordinariness. Its foreground is subtracted, diminished by squatty buildings, power lines, unloved yards and broken down cars.

We drove down to the church anyway and I asked Gary to take this picture in the dog hours of the afternoon. He didn’t have a wide-enough lens to document the surrounding squalor so this shot makes it look better than the harsh truth. The sun felt like it was peeling back my skin, branding me with disappointment. Even the graves to the side of the adobe church seem abandoned and overrun by time.

The same disappointment washed over me when we stopped at Francisco de Assisi – in Rancho de Taos. The view of this church that Georgia O’Keefe painted was never meant to be photo realistic. She isolated the lines, blended colors and smoothed shapes into the weathered strength she saw in all of New Mexico. But it had always been real to me, my favorite of all her paintings, until I saw it in person. It’s hemmed in by Taos now, buildings so close on three sides it feels claustrophobic.

It was under renovation when we arrived — the patched up adobe still wet and the smell of straw filling the air. In a way the construction debris made me feel better – this place is still revered enough for periodic face lifts. I have no right, I realize, to demand that time stand still for my benefit alone. I don’t even worship in these structures built by those who do. And that’s the crux of it. I’m clinging to an aesthetic while those for whom Hernandez and Assasi were intended experience it as a living house.

It was less unsettling, in a sad way, to find these ruins on our way to Georgia O’Keefe’s studio and house in Abiquiu. This once beautiful adobe outpost of faith is returning to a state of rest – dust to dust, literally. There are telltale signs that it will be missed – a giant handmade cross leans into a patch of dead cactus and someone tacked a rosary to a crumbling wall.

Perhaps, when it is gone, its absence will be more present than famous churches, forced to coexist and change along with us.

Caves of Time

The hiking brochure they hand you when you get off the shuttle begins with: “Evidence of Human Activity in what is now Bandelier National Monument dates back more than 10,000 years.”

I was about to embark on a trip back in time that made me question the nature of time itself. I’ve never been one to ponder many existential questions; I’m too busy setting goals and rushing to meet them to do anything but wonder where time went. But after a morning at Bandelier I’m no longer sure what constitutes wasting time. Consequently I probably am, just thinking about it.

In school, natural history never seemed as interesting as it did in the James Michener books I stole from my parents. But in the Frijoles Canyon history is mockingly relevant. I’ve felt the awe of National Parks before – the way places like Yosemite make you feel so puny and inconsequential. But at Bandelier it wasn’t just the physical grandeur of nature that humbled me, it was that damn first line of the brochure: evidence of human activity.

Somehow, in this most isolated and environmentally harsh place, ancient peoples not only survived but thrived. I was worried whether I’d get carsick on the shuttle ride out of the canyon but the Ancestral Pueblo people contended with threats monumentally more serious. The heat, for one thing. It reached 97 degrees on the day I visited — a dry, high-altitude heat that reminds you that a few days without water and you’d be a pile of bones picked over by coyotes. These amazing people, without the wheel or a single written instruction, literally carved a life out of a desert canyon.

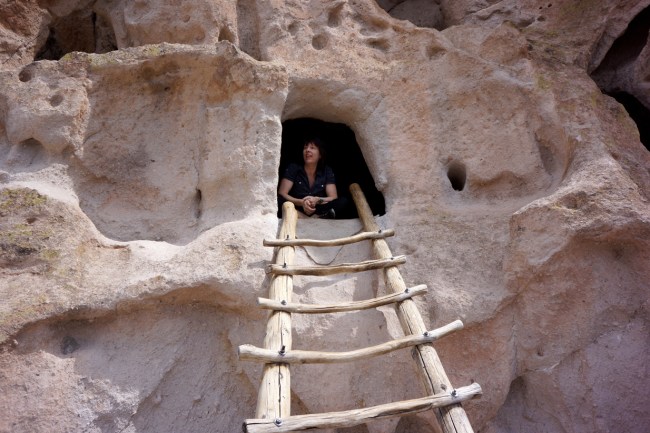

Which brings me back to the human activity part. The Ancestral Pueblo people figured out how to use tools to enlarge the openings of small, natural caves in the canyon’s cliff face. It’s called Tuff rock – the eroded remains of volcanic ash that compacted over time. It conserves the coolness of the desert night. It also serves as a permanent blackboard for ancient attempts at art. I say attempts because the figures and symbols seem less visionary and inspirational than utilitarian. If there were creative outlets for these ancient people they were stories, songs and dances lost to time.

You can still climb into the caves at Bandelier and see the discolored walls where fires burned thousands of year’s worth of nights ago. What stories got told around those fires? Were the cave dwellers dreaming of enough free time to pursue the arts or new worlds to explore? Or were they just staying warm?

What really gets overwhelming is when you sit in the cave openings and look out over the canyon valley floor. By virtue of a small stream these Native Americans did something radical – they raised crops to augment hunting. They built a village whose remains are still visible from the rocky overlooks. The brochure again:

“Imagine this village filled with the sights, sounds, and smells of daily activity. Women grind corn between two heavy stones. The air is filled with the enticing scent of ground corn as it bakes into delicious flat bread. Loud thumps reverberate in the air as a stone axe meets a heavy wooden beam. Men are busy constructing new homes. Children laugh and shout while dogs bark; together they herd turkeys and play games. As today, each person has his or her role and responsibility.”

I tried to imagine me in this village, ten thousand years ago. Would my life have had meaning or true fulfillment? What “human activity” would have kept me motivated? The Ancestral Pueblo people had religion- their faith was part of every aspect of their lives without sectarian separation. I do not identify with any one religion. I have no useful farming skills. I don’t even have children. If more than a weekend goes by without writing something I get fidgety. I feel like I’m wasting time and yet I have more of it to fill in the manner I choose than the Ancestral Pueblo could even imagine. It’s the mark of progress, we’re told, when labor becomes so specialized that not everyone has to spend their days on redundant, common tasks of survival.

Yet what does it all mean when “progress” means spending hours each day tweeting and blogging? It’s part of every writer’s job – building a platform so that readers will buy the books that keep publishers in business – so I’m not complaining. But is my multi-tasking life really any more advanced than the brochure’s hunting, weaving and heavy construction? My gut says no, but my brain says it is more fulfilling. I’m happiest when I’m swimming in the creek in front of my house — thinking of nothing and thankful for everything — but I couldn’t let myself float in that happiness if I didn’t spend the days planning the next project, the next challenge. I can change the circumstances of my life at will if my will is strong enough.

The caves of Bandelier haven’t left my thoughts since I returned to South Carolina. I keep going back to that cool, dark window on a world I can barely imagine. The closest I can come to understanding what the “human activity” of survival was like ten thousand years ago was how it felt when Gary and I drove through Latin America in a camper. Despite all my mental fidgeting and fastidious documentation for a future book, we had to stop driving by two each afternoon to begin the menial tasks of finding a place to camp, buy food, get water and bathe. I was happy. I learned I could survive without alarm clocks and internet access and deadlines. But would I choose that “simplicity” permanently? No. I need external stimulation like art and museums and daily challenges to what I think I know.

Bandelier made me appreciate just how little that is.

Canyon Road

I have been lucky enough to window shop along some of the most famous art streets in the world, from Paseo Prado in Madrid to West 27th Street in New York and M. Alcala in Oaxaca. But never has one road peaked my curiosity as much as Canyon Road in Santa Fe.

My “Other Mother” – Byrne Miller – lived in a rented house at the base of Canyon Road in the 60s, long before this 6/10ths-of-a-mile-road was the home of more than 100 upscale galleries. Back then it was a dirt road in the cheap part of town; many of the artists who lived and painted there built their own homes and studios out of adobe.

I tracked an address down from an old advertisement for the Byrne Miller School of Dance and set out to find the house where she danced and where Duncan began his third novel. But it turns out artists back then weren’t really into organization. The numbers don’t always go in order and some houses were torn down and replaced in different locations with the same number.

The closest I got was this cluster of buildings that now house two wonderful galleries. Somewhere behind me was the portico where Duncan paced and smoked his pipe while writing the Santa Fe Fiesta Melodrama and the kitchen where Byrne brought her dance students from St. John’s College for some home cooking.

What a heady time to be two artists in their nomadic prime. The Santa Fe Writer’s colony thrived from the 20s through the 40s… think Willa Cather and “Death Comes for the Archbishop.” D.H. Lawrence called Santa Fe home as well as the great poet Witter Bynner, who threw parties at his house for guests including Martha Graham, Ansel Adams and Georgia O’Keefe. Mary Austin’s “Casa Querida” was home to literary readings, salons and a fine arts school – and her own writing was very concerned with Native American rights.

The first Santa Fe artist’s colony owed its impetus to the Museum of New Mexico which held unjuried exhibitions for local artists starting in 1915. It attracted famous artists like Robert Henri, who showed in 1916 and 1917, and modernists like Marsden Hartley and John Sloan…then spawned a Santa Fe style local “school” with the 5 painters – los “Cinco Pintores.” You can still find their paintings for sale on Canyon Road.

By the mid 60s, when Byrne and Duncan arrived, commercial galleries had made Santa Fe a tourist destination, with the chance for artists to sell their work on a regular basis.

The owner of the gallery where I think Byrne and Duncan lived, Mark Greenberg, has family on Hilton Head but adores the town he chose to make his home. He’s on the board of the Canyon Road Arts Association and told me that in Byrne’s day, Canyon Road was as known for bar fights as painting – there was practically a shooting every weekend. Now there are as many famous actors in residence as painters: Alan Arkin and Gene Hackman have houses just up the street.

Byrne loved her years here. Duncan, not so much. The novel he began here is depressingly bleak, his query letters to publishers almost desperate in their defiance. It’s all a fascinating part of the memoir. Duncan was a Charleston SC native and he felt claustrophobic, without any bodies of water nearby. After a week in Santa Fe I felt the same. It’s a beautiful city, with incredible art and architecture, but so dry I literally had to stick my toes in the Rio Grande on a day trip out of town just to feel human again.